Back in August 2017, Moz’s Dr Pete published the Whiteboard Friday, “Aren’t 301s, 302s, and Canonicals All Basically the Same?”. Though it didn’t explore anything new as a concept within SEO, it did justifiably resurface an age-old SEO misconception that’s important to get right.

To reinforce Dr Pete’s argument, the short answer is no, 301 redirects, 302 redirects and canonical tags are not all the same. They’re each different with their own individual application. They share some similarities within the context of crawler control and reducing duplicate content, sure, but they should not be used interchangeably.

The simplicity yet importance of Dr Pete’s topic inspired me to write this article (so much so that I even included the Oxford comma within the heading as a homage!).

Similar to 301s, 302s and canonicals – crawl errors, 404s and broken links are yet another subset of terms within SEO that are often used interchangeably. Again, they are similar – arguably relating more closely than Dr Pete’s chosen comparison – but they each have their own definition which makes them all entirely distinct.

Let’s start by unpacking broken links before moving onto 404s and crawl errors. It’s at this juncture where we’ll then be able to discuss how each topic overlaps but more importantly, how each topic is distinctive from the other.

What is a broken link?

A broken link is a hyperlink present on a site that points to a non-existent or inaccessible page for both users and search engine crawlers. Broken links can either be inbound, i.e. pointing to internal pages on the same site, or outbound, i.e. pointing to external pages on another site.

They can occur for several reasons but most commonly happen due to the “linked to” page’s URL being misspelt, removed from a site, or where the URL has changed name/location.

The reason broken links are problematic within the context of SEO is three-fold.

- They directly impact user experience. Users click on these broken links and are met with pages that do not exist. This provides a frustrating experience that can potentially impact the trust between your business and your customers.

- When a search engine crawler accesses a broken link, it acts almost as a roadblock for them. This results in a bot conducting an inefficient crawl of your site. This can potentially impact your site’s crawl budget and can convey low-quality signals coming from your site.

- They impact the flow of link equity. Links are what tie the internet together, and it’s well-known that search engines use these to discover new pages and help rank sites in their results. This is nothing new, but it is, to this day, the fundamental reason why link acquisition remains a mainstay within SEO, whether that’s for internal or external link building.By linking to a page that isn’t accessible, you are cancelling the flow of link equity to and around your site. You are removing any perceived value that is attainable from links and therefore diminishing the ranking potential your site has.

For a link to be classified as “broken” it needs to be live on your site. It’s the interplay between the <a> tag, the href attribute and the physical link pointing to the inaccessible page that defines a broken link.

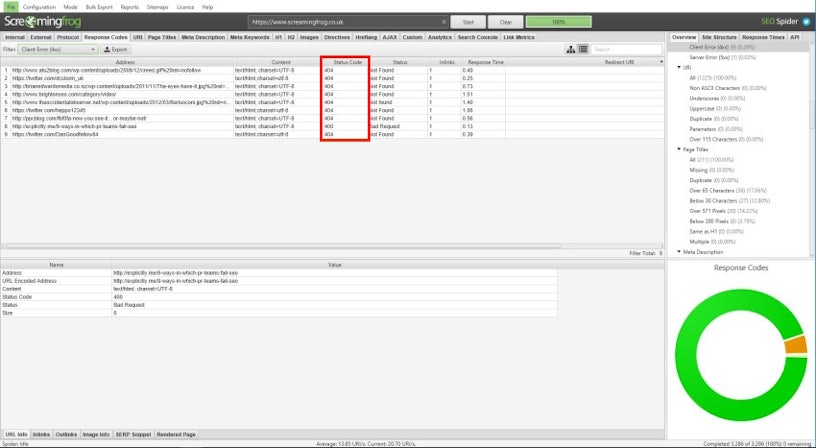

While plenty of broken link checkers (BLCs) exist, the most popular way of discovering broken internal links is by using Screaming Frog. The resource I have linked to explains thoroughly how to use Screaming Frog as a BLC, but in essence, you’re looking for URLs with either 4XX or 5XX status codes.

For external broken links, i.e. backlinks where other sites are pointing to dead pages on yours, I recommend using the “Broken Backlinks” feature on Ahrefs.

So, are broken links all basically 404s and vice versa?

Not entirely, and this is where I often see the misconception starting.

If a link is broken due to the URL defined having changed location then, yes, this is due to a 404 error. In this instance, the client, i.e. our browsers, is requesting something from the server that no longer exists and an appropriate 301 redirect will need to be set up to adhere to best practice. However, this definition is reductive and largely where many SEOs start to trip up.

In its most complete definition, a broken link needs merely to point to a page with any 4XX client error or 5XX server error to be classed as “broken”. Broken links, therefore, aren’t always exclusively due to 404 errors.

Both of these status code groups still create frustrating user experiences, create roadblocks for search crawlers and inhibit the flow of link equity. While the reasons as to why they’re problematic for SEO are similar, it’s their applications and resolves that make them different.

With a definition of 404 errors having already been established, below are some examples of further 4XX and 5XX status codes that an SEO will typically come across;

- 410 – Gone

A 404 status code does not explicitly define whether a resource has entirely gone for good. However, this is what is communicated when a 410 status code is used. Using 410s will convey that a resource has been definitively removed from the web and instead of search engines periodically revisiting it (as they would with a 404), it’s a sure-fire way of encouraging them to remove a page from their index. - 401 Unauthorised / 403 Forbidden

I have grouped these status codes together as they are both concerned with permissions and authentification. These status codes are typically used for staging sites or when access to some form of account is required. - 500 – Internal Server Errors

This is a generic status code used when a server-side error has occurred. Not only will this stop customer engagement but also search engines will no longer be able to crawl your site if a 500 error occurs. - 503 – Service Unavailable

The 503 status code signals that the server is currently overloaded or perhaps down for maintenance. While still an error, it is not an absolute as it communicates to both users and search engines to come back soon when the server is live again.

For more information on status codes and the other classes and categorisations available, see this comprehensive resource from Wikipedia.

Though broken links need to be live on a website to be referred to as broken, 4XX and 5XX errors can still stand on their own and be discoverable via other means.

As an example, consider a web developer who has created an orphaned page for whatever reason. They haven’t linked to the page internally due to the nature of the campaign it promotes, but it is available via the XML sitemap (thus, making it indexable). If the page gets deleted so will its reference on the XML sitemap. Broken links are not therefore applicable in this instance, but the resulting 404 status code is still discoverable by a search engine.

Hopefully, the example above sufficiently highlights how the definitions of broken links and 4XX and 5XX errors are not interchangeable. Both entities need to be considered as separate to one another to be classified correctly.

There is an element of causation and non-mutual exclusivity here as some form of “link” needs to be present to find 4XX and 5XX errors in the first place (from a search engine perspective anyway) but it is not entirely correct to define 4XX and 5XX errors as broken links and vice versa.

So, are broken links and 404s all basically crawl errors?

Yes and no. While broken links and 404s are crawl errors, there’s also much more to crawl errors than that.

Crawl errors are synonymous with Google Search Console and its Crawl Error Dashboard found on the platform. It’s within this dashboard where Google flags any issues that are resulting in some form of error when Googlebot is attempting to crawl your site. As we know, if Googlebot is finding any errors whatsoever when it’s attempting a crawl then it’s well worth taking note.

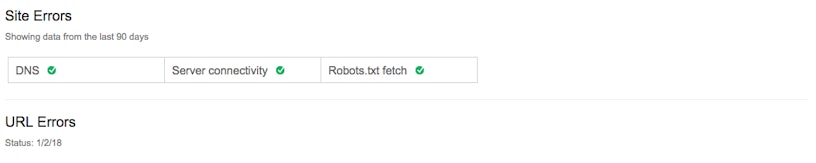

So, while a crawl error can constitute everything so far discussed in this article, from broken links, 4XX, and 5XX errors, they’re more of a subset known as “URL errors”. It’s again reductive to classify these three elements as the only reasons for a crawl error to occur. Crawl errors can also occur through ‘Site Errors”, which Google classifies as something being wrong with your DNS setup, server connectivity or robots.txt file.

Search Console separates “Crawl Errors” into both “Site Errors” and “URL Errors” for a more holistic view of what’s causing crawler problems on your site.

Put simply, anything that is stopping Googlebot crawling your site properly can be classified as a “crawl error”, whether that’s a 404 causing a roadblock or an entire directory being disallowed via your robots.txt file.

So, why does all this matter?

You may be inclined to believe that this is all down to semantics but getting these types of definitions right does matter.

Whether you are experiencing broken links, 4XX/5XX errors or crawl errors, they all need to be fixed to improve your site’s user experience, crawl efficiency and link equity flow. However, using the correct definitions will lend a hand in allowing the right diagnosis to be communicated. This will then result in implementing the correct fix and most importantly, allow you to allocate the appropriate level of resource and time to solve the problem.

To conclude, this post was influenced by Dr Pete’s dedication in getting the definitions of 301s, 302s and canonical tags correct. What other SEO issues do you come across that are often misinterpreted? Let me know via Twitter and let’s get the conversation started!